The Imitation Game

Complexity studies physical processes that are generally unpredictable or difficult to predict and depend on many interacting degrees of freedom. Examples include chaos, rare events, brain functions, natural mimicry and camouflage, swarms, cooperative dynamics, intelligence, etc.. Despite that, in some cases, the evolution of these systems seems dictated by relatively simple interactions—such as predator-prey games in nature or neurons that send electric stimuli to their nearest neighbors—the effects arising are advanced and sophisticated, with a common denominator: extreme efficiency and sustainability.

A brain with 250 trillion connections and 100 billion neurons is contained in a cube of only 10 cm side, consuming less than 20W. Each neuron dissipates less than one nW: this power is one-millionth the one dissipated by the most sophisticated transistor fabricated today. A similar complexity seems to rule unpredictable natural phenomena, such as chaotic Brownian motion or catastrophic events. Rare phenomena ranging from hurricanes to anomalous water waves originate in environments that are normally in a calm state. Under specific conditions, strong cooperation among many waves in the ocean or clouds in the sky occurs, triggering the formation of events that gather exceptional amounts of power. The equivalent power of each of these events is way higher than the most efficient plant available on earth. The camouflage of specific mollusks is more advanced than the most sophisticated nanomaterial engineered today; they can also dynamically change, contrary to manufactured best structures. Ants explore a given terrain faster and on higher grounds than any current technology based on drones. Each ant also requires an infinitesimal amount of energy. Human babies develop spontaneous language abilities and cognitive thoughts, which do not happen in the most advanced technology platform currently available.

The goal of our research is to understand the physical origin of these behaviors and transform them into sustainable technologies that tackle the contemporary problems of global interest, ranging from energy harvesting to clean water production, design of smart materials, biomedical applications, information security, artificial intelligence, and global warming.

If successful, this could unlock advanced functionalities resulting from millions of years of evolutions and optimized adaptations. The importance of this research has already been recognized decades ago by Warren Weaver in a famous paper:

“The future of the world requires science to make a third great advance, an advance that must be even greater than the nineteenth-century conquest of problems of simplicity or the twentieth-century victory over problems of disorganized complexity. Science must, over the next 50 years, learn to deal with these problems of organized complexity.“

W. Weaver, “Science and Complexity“, American Scientist 36, 536–544 (1948).

Creating technologies from complex natural systems is a modern interdisciplinary research field that permeates many different scientific areas. In electronics, extensive research efforts study living cells and genetic networks for developing efficient superconducting circuits. Complex network structures can also optimize power consumption on electrical grids, communication protocols, and social media. In economics, the study of complex interacting systems profoundly impacts several areas of interest, including logistics and finance. In mechanical engineering and materials science, biological systems’ high degree of sophistication replicates to develop materials and devices with remarkable performance, as in the case of bio-inspired surfaces for water condensation. Neuroscience significantly investigates the structural properties of the brain to create future technologies in medicine and neuromorphic computing. These results’ maturity also led to a reborn of interest in artificial intelligence, attracting billions of dollars of funding from governments and private industries.

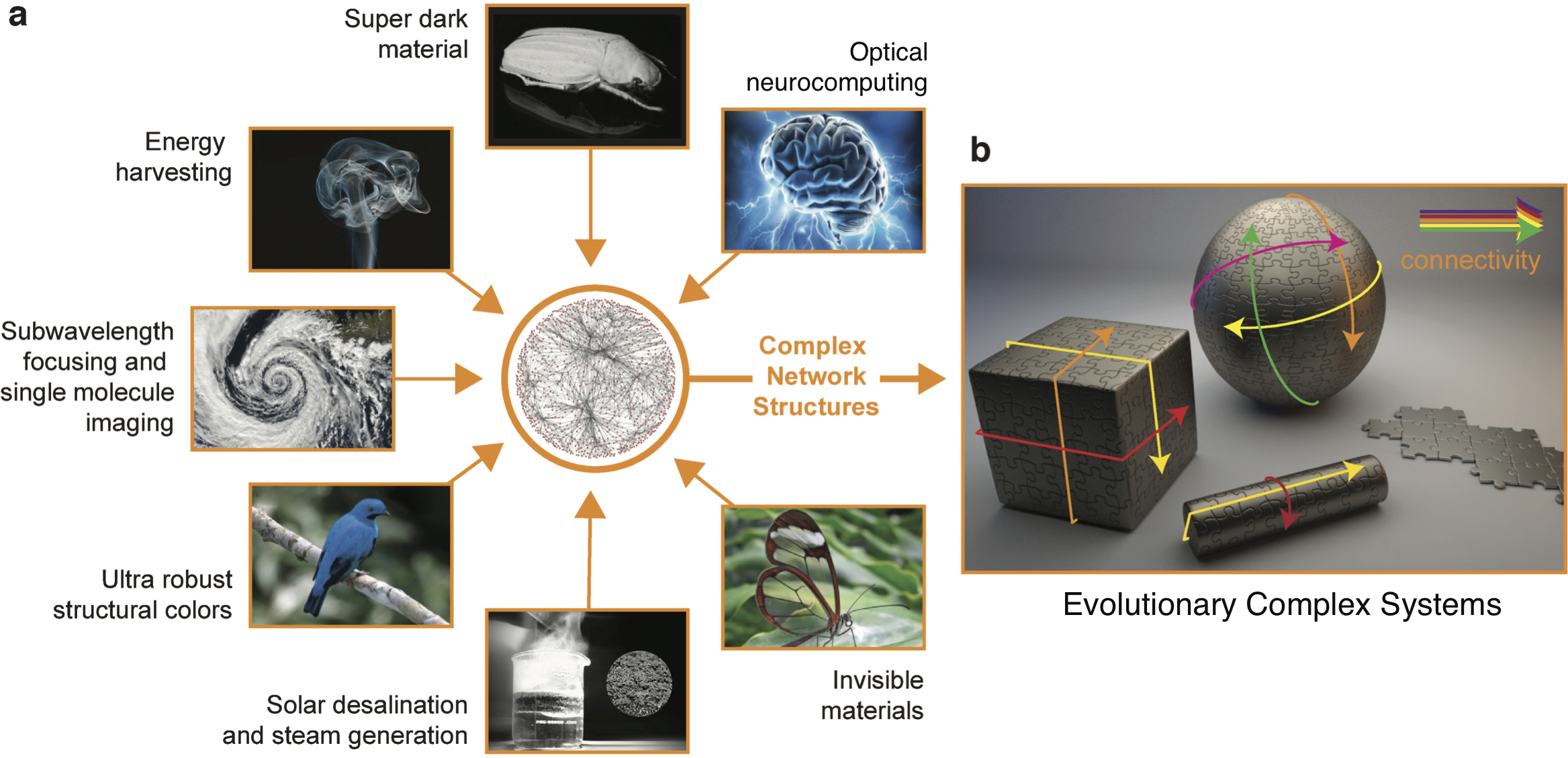

Figure 1. Conceptual description of Evolutionary complex systems applications.

Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of evolutionary complex systems and devices. Figure 1a shows different complex Natural systems ranging from chaotic dynamics to catastrophic events, neural networks, and sophisticated camouflage techniques of insects and birds. Unlike classical structures, evolutionary systems leverage many interacting degrees of freedom (Fig. 1a). These correspond, for example, to a complex network of electromagnetic modes driven by chaotic dynamics, or to a large multitude of interacting waves in a rare event, or a multitude of disordered nanostructures following the structure of natural insects or birds.

By leveraging on a “nonlinear orthographic” design concept inspired by the structure of these systems (read more here), we realized high-impact applications in several fields, ranging from energy harvesting to bio-imaging and complex material engineering (more information on the research section).

Figure 1b shows a possible pictorial representation of an evolutionary complex system. This system is a multidimensional structure created by different components’ interaction (i.e., the connectivity in the language of network dynamics). The system’s response is visualized as a specific shape created by the parallel interaction among all the elements of the multidimensional network. By changing the connectivity in one step, the system can assume different responses and manifest diverse behaviors.

This design approach allows relaxing many fabrication constraints, as the single atomic units of the network are typically heterogeneous or disordered elements, which are easily scalable. Large-scale network structures are also highly robust. The organization in a multidimensional network structure can easily absorb single units failure, given the possibility to change the system connectivity and restructure the network interactions to maintain the network functionality even under harsh conditions.

Another attractive feature of these systems is that they typically exhibit a characteristic number of states that grow exponentially with the system’s size. An example is a foam structure, which possesses an exponentially large surface for a given volume of material. This property is advantageous over materials assembled from arrays of identical elements, whose characteristic properties scale linearly with the system size. In a complex system, this advantage typically translates into a nonlinear (e.g., exponential) efficiency. These are usually not attainable in traditional, non-complex systems, which exhibit linear efficiency increase with the system size. Read more here.

The exploitation of complex systems to build new technologies is a challenging yet promising research field. It involves understanding what we consider complex, which translates as something involved, intricate, complicated, not easily understood or analyzed. This diffculty sets the challenge of understanding the mechanisms of these systems and crossing many different disciplines to harness their properties into technological applications.

However, when these dynamics are suitably understood, even to a few percent, our results show that it is possible to engineer devices with record performances in fully scalable platforms, offering a promising approach to address global challenges with new sustainable technologies.

Read more in:

Favraud, G. , Gongora, J. S. and Fratalocchi, A. (2018), Evolutionary Photonics: Evolutionary Photonics for Renewable Energy, Nanomedicine, and Advanced Material Engineering (Laser Photonics Rev. 12(11)/2018). Laser & Photonics Reviews, 12: 1870047. doi:10.1002/lpor.201870047

A detailed analysis of the advantages and challenges of these systems is also presented in our article on nonlinear orthography.